|

A DREAM OF STARS AND LIFE, PART 2

By PHILIP ANDERSSEN Published: Tuesday, 11 December 2012 |

|

. . .

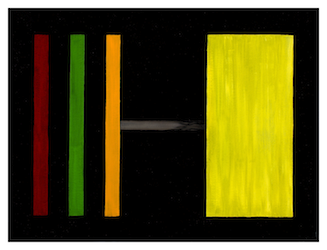

It is precisely this lack of rules that grants interpretation unrestrained freedom. “It’s one of the great things about great works of art that they can bear—and, indeed, that they invite—a superplenitude of possible readings, some of them contradictory” (Weschler 59). Is it? Isn’t it instead the very criticism the one that creates a superplenitude of meanings because of a complete absence of rules for interpretation? When conventions are in short supply interpretation seems to run for refuge to the subject that interprets, and it is then when “the mind takes charge instead and goes off on some alien vision” (Forster 261). The act of interpretation is then redirected and takes as its pivot not the painting, but the very individual; limitless possibilities, as well as ubiquitous contradictions will promise to saturate interpretation. Susan Sontag, in her essay “Against Interpretation,” realizes this when she describes interpretation as an act or gesture of the mind that must be itself also evaluated because of its dependence on the individual or perhaps the society (758). How do we solve this dilemma?

The clue to it is to appreciate the nature of art. We must realize that art lies in a realm of expression, a state of creation, where the artist dwells for what is new; he strains for fresh ways to verbalize his happiness, his sadness, his rapture, his grief, his love, his fear, to make them unique. We may recognize these feelings—in fact they occur to any person—but the artist transforms the way of expressing them: with art he will use this image or that because it begets certain feelings. But it is ultimately his call. The artist will develop his own rules, rules of creation, his rules. “If you stuck to the rules and nothing else, what could you achieve?” (Callow 245). It would seem then as an mysterious and pointless activity to try to discover these rules, but the artist doesn’t conceal them: they are there, on the painting, but they speak with the language of expression, a language that we must first feel before trying to grammatically analyze. “Unfortunately this infection, this sense of co-operation with a creator, which is the supremely important step in our pilgrimage through the fine arts, is the one step over which criticism cannot help' (Forster 117).

“The Starry Night” was shouting to be heard, but interpretation was here as a start point the most futile of the possibilities. What convention could I use? I had a sense that this painting was crammed with rules, Van Gogh’s rules, and they were there, somehow, because he placed them there. I just had to see.

This is what I see.

A priori is a transfigured night sky what inundates the eye: a vast part of the canvas is just covered by it. An emotional sky, thunderous, turbulent, violent. A sky that overpowers the unprepared mind. What draws me the most though, is not just some sense of infinity that inspires in me, but the “great coiling spiral nebula” as Meyer Schapiro calls it, a gigantic and fantastic revolving shape of blue that irrupts into the sky swallowing what’s in the way. The sky is colored by eleven magnified stars and a rather strange moon as well. It is a moon-quasi-sun, as if the moon and the sun were interlocked in a struggle for supremacy, evoking in me an intense feeling of turbulence. The only part of the foreground that we can see is the upper part of a cypress tree, flickering as fire in its full greatness. Down below, a quiet town protected by wavy hills seems to be misplaced: there is no movement, except for the church: it has a spire that shoots into the sky, reminding me again of the cypress. . .

Callow, Philip. “Chapter 12: Asylum.” Vincent Van Gogh, A life. Ed. Ivan R. Dee, Inc. Chicago, 1990. 239-262.

Forster, E. M. “Not Looking at Pictures.” Encounters: Essays for exploration and inquiry. Hoy, Pat C. II and Robert DiYanni, eds, Second edition New York: Mc Graw-Hill, 1997. 261-263.

Forster, E. M. “The Raison d’Etre of Criticism in the Arts.” Two Cheers for Democracy. Ed. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. New York, 1951. 107-123.

Sontag, Susan. “Against Interpretation.” A World of Ideas: Essential Readings for College Writers. Ed. Lee A. Jacobus. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s, 1998. 754-765.

Weschler, Lawrence. “Inventing Peace.” The New Yorker. Ed. of November 20, 1995.

comments powered by Disqus

| RELATED ARTICLES | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||